Remembering the Enslaved

Valery Small reports on Liverpool's new museum

The keynote address at last October's opening of the gallery dedicated to the transatlantic slave was given by Dr Maya Angelou. In her humorous, painful and elegant style, she urged Black people neither to fear nor forget the legacy of our enslavement but to use it to be strong.

"History," she said "despite its wracking pain, cannot be unlived but, if faced with courage, need not be lived again."

This theme, using the experiences of the past to forge ahead, was carried on by Liverpool-born Eric Lynch, who paid homage to his ancestors who gave their lives for his freedom.

"It might be difficult to forget those 500 brutal years," he said, "but we must use them to be strong. You see before you the result of slavery. You see a black man in the clothes of a white man. You see a Black man who cannot speak the language of his ancestors. I'm here to honour my ancestors - not the Europeans because of whom I am here, because of whom I now bear the name Eric Lynch."

Dramatic evidence of tangible links with the past came when Naa Marteke Bukom, a decendant of Ga nobility and a high priestess, at the gallery to pour libation, recognised one of the enslaved, mentioned in the exhibition, as a member of her family.

The gallery, located in the basement of the Merseyside Maritime Museum on the Albert Dock, next door to Granada TV studios, is not without controversy. A number of local Black groups, for instance, opted to boycott the opening. They are sceptical of the supposed benefits for the Black communities. They accused the gallery of not taking into account the wishes of the community. It was also suggested that the museum had been hijacked from grassroots Black organisations which, in the final analysis, had been excluded. This dissent may not prove significant in the long run, but to date, the visitors have been mainly white.

'there are no memorials for the thousands of Black people who perished in the middle passage'

The lack of involvement of many Black people goes deeper than their inability to obtain invitations to the opening ceremony. A straw poll conducted by Black Perspective revealed that while many people had heard about the museum, none of those we spoke to believed it had anything to do with them and did not intend to visit it. Some elders were adamant that they had suffered enough throughout their lives because of their legacy and they did not wish to be reminded of the horrors. "It must be time," one 79-year-old said, "for us to let our people rest in peace."

But that is precisely the point. As the poet Kamau Braithwaite reminded us recently, there are no memorials for the thousands of Black people who perished in the middle passage. The only memorial of the "indelible stain of slavery" is the hue of our skin and our psychological scars. Without a tangible acknowledgement of our loss, we cannot leave our ancestors to rest.

Both Liverpool and the Albert Dock have long associations with the transatlantic slave trade. The Docks are infamous for both building and repairing slaving ships. It was almost certainly from here that John Newton captained ships that sailed along the triangular route. The city, like Bristol and London, was built on the proceeds of slavery, the legacy of which can be found today in its architecture. African heads adorn the Town Hall and street names reflect this past.

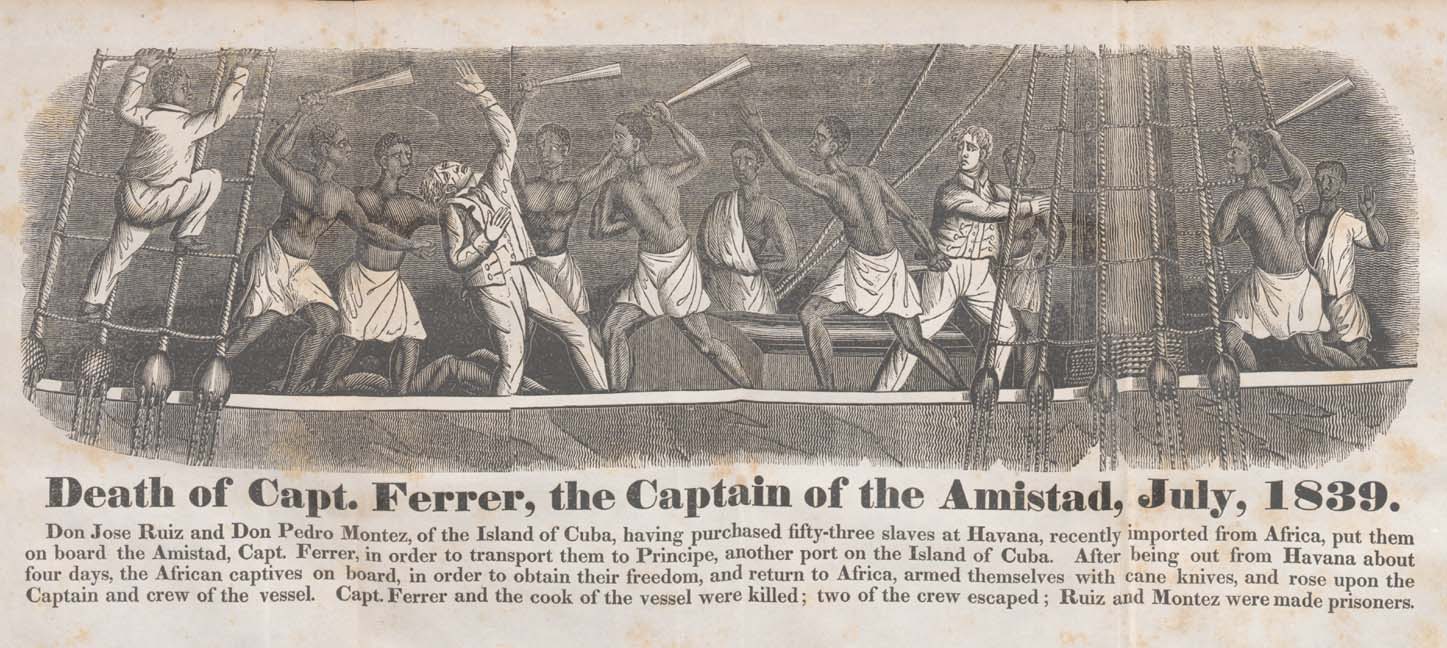

The exhibition uses the latest in mixed media technology, with readings from autobiographies of the enslaved and slave owners alike. Real sugar cane plants are displayed, to re-recreate a plantation walk. Cut-outs of individuals, adults and children, named and dressed in traditional West African clothes personalised the exhibition, lest we forget that the enslaved were people. But the piece de resistance has to be the reconstructed hold of a slave ship through which visitors walk, crouched, in semi-darkness. Probably the most telling thing about this walkway is the notice at the entrance, informing visitors that the height has been raised by 6 inches to comply with fire regulations. It takes a few minutes to walk through the hold. Imagine what it must have been like for the survivors who for months on end were stacked like sardines in a similar dark and cold underwater hold.

There have been numerous unsuccesful attempts to sanitize slavery. Europeans used fear, violence, rape and torture to quell personality and break the will of millions, strip them of their heritage as Mandingos, Yorubas, Igbos, Ashantis; turn them first into Africans, Negroes, and then slaves. With each transformation, a bit more identity, a bit more self respect was taken away. As slaves, they were reduced to commodities to be traded or bequeathed in wills as it pleased the "owner".

There is sufficient evidence to justify these claims. Yet there are still some who quibble over actual numbers or whether it merits the term 'holocaust'. Others excuse the Europeans on the grounds that Africans were involved in their own enslavement. However as Zairean historian, Elika M'Bokolo, points out, the trade was essentially a one-sided relationship founded and maintained on the threat of force.

The English, Portuguese and French, although declaring that the slave trade was justified when it involved slaves sold by Africans, nevertheless built forts along the coastline in order to organise the trade and at the same time instill fear into the Africans. The message was clear - "Sell us slaves and we shall leave you to chose them as you see fit, or else we shall take what we need at random.. "

Many Black people are uncomfortable with the half a million pound gift from the Peter Moores Foundation to set up the gallery. However although a single gallery cannot be expected to expunge 500 years of horror, there are positive aspects to it. The legacy of slavery is as much that of the white communities as it is of the Black. This is an opportunity for both to take a closer look at what it entailed, at the instruments of torture, at the proceeds of the trade, and reflect, lest we ever forget that it happened.