Not Yet Freedom: A short story of struggle and disappointment

He was fiery and stubborn, that one. He fought and fought - even when he could not win. Even when everyone saw that he could not win, he fought on. And his people came to him and said: "Nkenga, look at your wife, look at your child. They suffer because you are fighting a war that you cannot win. What do you seek? Is it not happiness and contentedness? You have the white man's education and, like Joshua and Nguigi, you can live happily and leave the struggle to fate."

"And he replied: "Happiness and contentedness? What is happiness and contentedness? How can I be happy with so much injustice surrounding me? I want to be happy and so I have to struggle to put things right.

And they said again: "But brother, leave all to fate. Don't you know that however hard you struggle, whatever will be will be."

And he sneered in the face of destiny - a thing our fathers never did. He said: "Destiny? What is destiny? Why do you pick up your hoe if your future has been foretold? Besides, if it is destined that I will die struggling, why then fight against it?"

Then they said again: "Please, brother - "

And he replied: "Let me be." So they left with a sigh. He was a stubborn one, that one.

Some say he got it from his father. His father, Kamau, who stood up to the white man and said: "Our fathers never paid tax to anybody. Who are you to come here and levy our land on us? Go away with your taxes." His father who said: "Why should I bow to a king that I don't know; a king who has not fed or protected my family but has sent his soldiers to steal our women?"

The white man's army took Kamau and whipped him. They caned him again and again, and when he did not stop, they threw him into their dungeons. But when he eventually died, with a curse to the white man on his lips, the white man - those cunning people - , they took his body to the open square and called out the people. They praised his courage and said a lot of good things about him and cried a bit and the villagers cried, too and began to say: "The white man, maybe he is a good man after all." But that was years ago when Nkenga was still a suckling and no one told him these stories until they saw he was like his father.

Nkenga fought the white man. He had the white man's knowledge and fought them in their own language until his own people did not know what he was saying. Then the white man grew angry and threw him into jail - just like they had done to his father - but still he fought them, in their own courts until they let him go. They began to fear him and side-stepped when he passed. Some even called him "Sir!" Oh, what wonders!

"Our fathers never paid tax to anybody. Who are you to come here and levy our land on us? Go away with your taxes"

But he kept on fighting them. Then, one day, they packed their bags and left, fed-up, and the people once again ruled themselves. Then Nkenga said: "I am happy. I have achieved my goal. Now my struggles can stop." He went back to the white man's land - where he taught them their own knowledge!

The people sighed, happily. Their own people now ruled them. Things would be okay now. They waited. First day; second day; third day..... and nothing happened. They waited, but hunger and want came upon the land. And these new rulers, they asked for taxes too. "But taxes are the white man's food. What do you want them for?" But they seized anybody who refused and beat them up just like the white man did.

They took the land away from the people and locked up all who resisted, just like the white man did. They did all they did, just like the white man did. "Did you not promise us that the white man's ways would go with him?"

Then, one night, Kolo and his gang sneaked into the presidential palace where the leaders lay asleep, but they were caught. They said: "We only wanted to touch them to see whether the white men rubbed their skin with charcoal."

They were killed. Brutally. Even the white men did not do that. No, not here. So lunatic fear was let loose upon the land and sadness reigned.

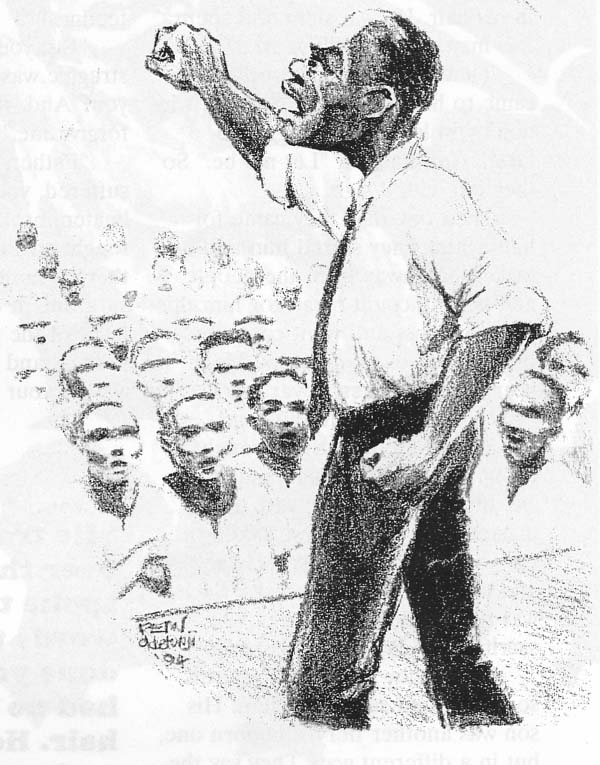

Then one day, a name from the past came upon the lips of the townsfolk: "It's Nkenga! It's Nkenga! He has come back from the white man's land." And, true, Nkenga came, much aged. He was breathing steam and the people knew there would be trouble. He spoke. He spoke and spoke like he used to, not changed one bit by his grey hairs. He was a fiery one, that one.

Yes, he went all over the land, and spoke to the people. I remember one cool morning, in the valley between the rugged folds of the Murongo hills which slope slowly down to the muddy banks of the great lake Victoria. I remember that day because his words were the most beautiful I have ever heard and - you could tell - they were the most beautiful the rest of the crowd had ever heard, too.

He stood on the highest rock in the valley, his back to the large, red, rising sun which spread it's rays up from behind him and cast him in a soft, beautiful silhouette. He was like a messiah.

"My people, I greet you. I have given up my all to come down here because I can no longer sit and wonder how long you will remain under the bondage of evil and repression....."

He spoke and spoke and spoke until he went down with the fever, but he still kept on talking. He travelled all over the land with the same message and wherever he went, a new vigour rose in the people. There was light in their eyes and fire in their hearts. They chanted and ran along the streets with branches in their hands. And the leaders grew afraid.

The leaders grew afraid.

Then one evening, when he was talking to the people of Northwest province, the policemen came, cracked his head and took him away. They locked him up just like the white men did to him. For many years, they kept him in jail. His people pleaded for him and his white friends - so many of them - they pleaded too. So he was freed one August morning and the next day, he started to speak again. He travelled all over the land and spoke the same words that he had done years before. He had no black in his hair. He was bent and spent, this man. But he still spoke.

That was when his brothers came to him and said: "Nkenga, why don't you leave the struggle to fate?" And he said, "Let me be." So they left with a sigh.

Then one day, they came for him again. They seized him and locked him away from the people and no one could plead for him this time. Sadness and want continued in the land for many years. Many years. Our children never knew what it was to go without want.

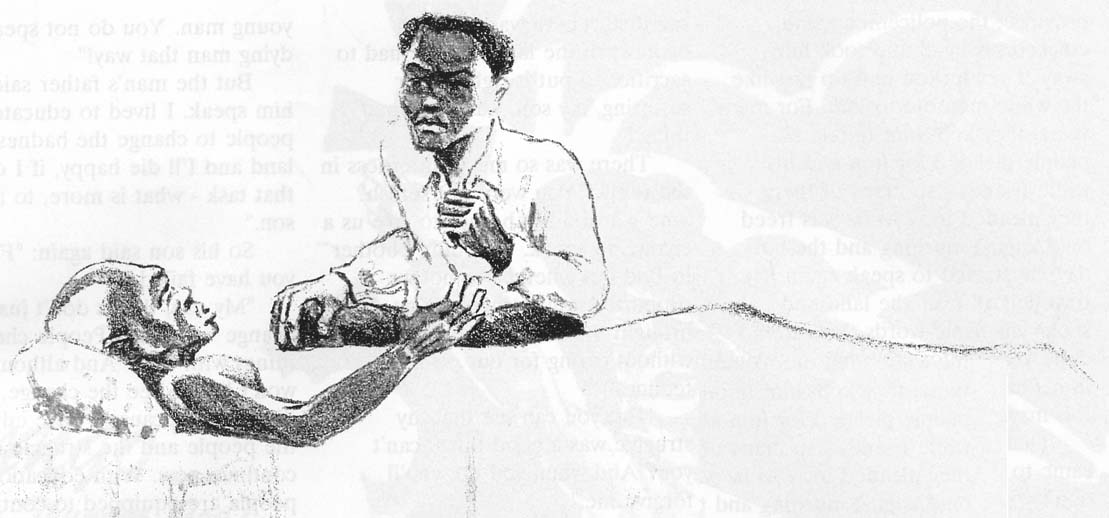

Some time ago, they brought a dying man to our village and when we, the old ones, said, with a distant light in our eyes: "Nkenga!", the young men said, "Who is he?" and went on with their tasks. Such was the tragedy of the man who sacrificed so much for his people.

When they laid him down, his son came and sat beside him. His son was another fiery, stubborn one, but in a different way. They say the white man called him a social misfit. He said, "Father, they did this to you?" and his father said, "Yes, son. They've killed me."

The young man said again: "Is it true that my uncles tried to stop you?"

"Yes, it is true, but they did not understand."

"So it is true that they tried to stop you and you did not listen - even when they told you that we - my mother and I - were suffering." There was bitterness in the young man's voice.

"My son, I suffered, too. I suffered more than anyone present. I was not selfish. I knew you suffered, too, but we all had to sacrifice. There was so much badness in the land that we had to sacrifice to put it right. Your suffering, my son, was not a bad thing."

He travelled all over the land and spoke the same words that he had done years before. He had no black in his hair. He was bent and spent, this man. But he still spoke.

There was so much bitterness in the reply: "You were not selfish? And you did not bother to give us a chance to speak. You didn't bother to find out whether or not we supported your struggle. You brought me and my mother into this without caring for our own feelings!"

"But you can see that my struggle was a good thing, can't you? And when you do, you'll forgive me."

"Father, you fought, you suffered, you sacrificed. You were beaten, broken, bent. But what you fought against, father, it is still there. There is sadness and suffering in the land. Look at the faces of the people. There is sadness and suffering. You've wasted your life and you've wasted our lives. You are dying and I am dying but the fear and the sadness still remains in the land. Your struggles, sir, have failed!"

There were many elders in the room, and they shouted: "Shush, young man. You do not speak to a dying man that way!"

But the man's father said: "Let him speak. I lived to educate the people to change the badness of the land and I'll die happy, if I die in that task - what is more, to my own son."

So his son said again: "Father, you have failed."

"My son, things don't just change with time. People change things with time. And although I won't live to see the change, I will die happy because I have educated the people and the struggle can continue now. With education, the people are equipped to continue and when they do, the change is bound to come some day. I am happy, son, because I have done my bit for the change."

"No, father, no. If the change will come, then you will have struggled well. But the change will not come. The struggles of honest men are in vain because of bad ones. It is so easy to destroy what honesty laboured to build and so any struggle for justice will be futile.

"The badness in the land is the badness in man. Anyone who tries to destroy the badness in the world tries to destroy, in man, the greed, the jealousy, selfishness, and cruelty. This is not possible. These very things are man.

"The world was built to be evil. Can't you see, father. Otherwise why did God allow so much badness in man? Can't you see that the struggles of a honest man in this world are in vain? Can't you see?"

Maybe he saw or maybe it was because he could not make his son understand because, they said, when he died, there was such anguish on his face.